Navigating Alzheimer’s with Compassion

Mum’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis wasn’t a shock, but it was still tough to take.

We knew her cognitive abilities were declining: It started with confusion around dates. She misplaced her car in a small parking lot while shopping for groceries and called to ask me what colour it was. And then she stopped remembering to make herself dinner. She got thinner and started to fall.

She’d call my brother and me, confused and crying, wondering where she left the cash for the gardener. She was overwhelmed.

She could no longer care for herself, and we knew it.

My brother and I discussed moving her into a long-term care facility and touring several places near us. Unfortunately, COVID-19 had made me nervous about long-term facilities. The only things I’d heard about them in the media were negative – linked to so many deaths.

Thanks to the tours and staff, my mind was changed. I had worried about residents being ignored, but these residents received a great deal of attention. We were struck by the kindness and the fact that many nurses working in these assisted living centres knew all the residents by name.

“Of course! We’re working in their home!” One nurse explained to me. I loved this perspective.

Mum agreed to move into a residence outside Ottawa without much fuss. We took her for a tour and a dinner, and she fell in love with the people there. After her husband died in 2020, she had been isolated; she missed having people to talk to.

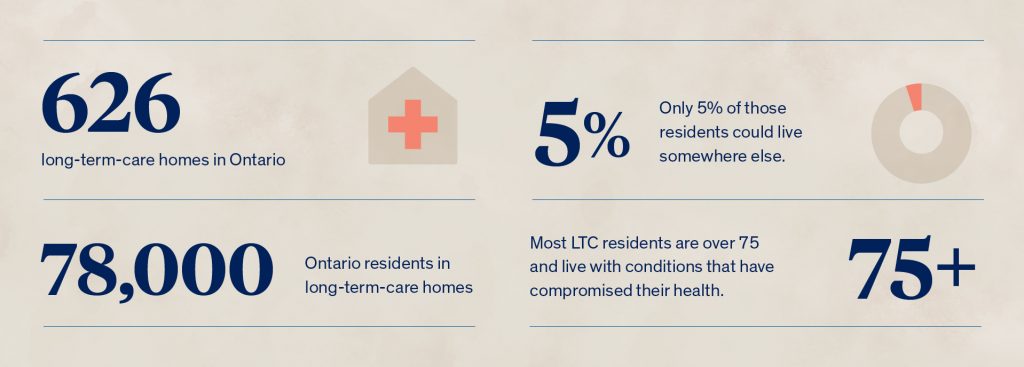

According to provincial statistics, 626 long-term-care homes are home to more than 78,000 residents in Ontario. Most LTC residents are over 75 and live with conditions that have compromised their health. Only 5% of those residents could live somewhere else.

While she has been there only two months, Mum now raves about the food, the other residents, and the nurses.

I recently got to speak with Brianna Kennedy, an RPN working full-time at Victoria Manor in Lindsay, Ontario. That Mum is so taken by her caregivers isn’t a surprise to Brianna, who says that talking with the residents is the highlight of her shift.

“Honestly, making the residents smile and feeling happy when they see you is the highlight of my day,” Brianna says.

I tell her how impressed I am with the nurses who work with Mum and how they know everyone’s names. The flip side, of course, is that Mum rarely remembers theirs.

“That’s okay. I’m okay with that. It’s cool to see people with Alzheimer’s, even if they don’t know your name but know you. And they’re like, I see you, and I love that.”

For Brianna, being able to make a difference in somebody’s day is why she loves working at Victoria Manor and with its 166 residents. That was her mother’s advice when she became a nurse: make their day.

Brianna’s mother was a nurse for 30 years at a similar long-term care facility, and she inspired her daughter to go into the field.

Although WeRPN’s Bridging Educational Grant in Nursing (BEGIN) program funded part of her nursing education, Brianna started at Victoria Manor in high school. She started her career by running the activities program for five years, then working as a Personal Support Worker (PSW) while in nursing school. In partnership with the province of Ontario, the BEGIN program inspires and enables PSWs and RPNs to become RPNs and RNS and to explore new opportunities in Long-Term Care and Home and Community Care.

While her goal since childhood was to be an RPN, she wanted to be a PSW first. For her, it gave her the foundation she wanted to reach her dream.

As an RPN and a behavioural specialist, she loves being able to work with her residents closely.

“I loved learning the stories behind all these people and getting to know them. As much as the dementia is sad, I enriched their lives with some kind of happiness,” she says.

I thought about my mother, who, while in the early stages of the disease, clings to the memories that are easier to call upon – those from the distant past. She loves to talk about being a teenager in Glasgow or her work on the Scottish island of Iona.

I can imagine how happy she would be to have someone like Brianna to talk to.

Brianna works in a BSO role, focusing on behavioural support.

“It’s a little outside the normal nursing, but you look at a person outside the box. If someone has responsive behaviour, I examine why they are doing that. It could be a UTI; maybe their back is itchy. It’s nice to be able to look around the person, see what’s going on, and help them live comfortably.”

And this is where I paused. I’m not a nurse. I’m the daughter of a person with Alzheimer’s and dementia. So I had to ask Brianna: can a UTI affect behaviour?

It can, she explained.

At this point in the interview, I realized why we’re so lucky to have Mum in a place where people can care for her. Alzheimer’s is new to us, but the nurses and PSWs at her long-term care facility are well versed in what it looks like – and why little things like the lights going off on motion sensors in the laundry room might set her off.

I lost track of my questions and thanked Brianna. I don’t know how she can do what she does. Loving my mother doesn’t mean I’m fully equipped to care for her twenty-four hours a day.

“I’ve interacted with some families that say their parent’s dementia is now worsening. We do a lot of supporting with the family and educating them that this is a disease process,” Brianna says. She says her role is to support the resident – and their family.

“So, for example, a resident is randomly becoming aggressive, and they’re angry and swearing, and that’s not normal for them. The family may remember their parents as calm and quiet, and we explain that that’s not them; that’s dementia. We try to support them in the transition of the disease process.”

Brianna explains that in her department, in the locked memory care ward, two RPNs and three PSWs are working to deliver care. They visit with residents to learn more about them, do depression ratings, watch their gait to see if they’re a fall risk, and make sure they are comfortable.

I know this is where Mum will likely end up as the disease progresses, and I’m comforted by the thought that a nurse like Brianna will care for her. I asked her about working in the memory care ward.

“I think it takes a lot of patience to be on that unit,” she says quickly. “They wander. There’s a lot of wandering. They’re up in your personal space, so you need much patience. I think residents are not as easy to redirect.”

But the most challenging part, she says, is not to get attached to the residents she’s working with.

“They always tell you not to get attached. I can honestly say a challenge is watching them deteriorate more,” she says. While doing a student placement, Brianna recalls a resident who had just been diagnosed with the early stage of Alzheimer’s. She kept asking for brochures every day to understand.

“There would be days of severe paranoia, and then the other days she’d be okay and crying like she knows what’s happening. That’s the challenge. The later stages you can work with, whereas the early stages are tough to watch because they know. They’re aware.”

The comment hits home. In January, Mum told my brother and me she thought she had dementia. Some days, she will joke about it. Other days, she tells me she can’t believe how confused she is. This is a brain disease.

“Just live in her world,” Brianna advises. “Don’t ever try to reorient them, especially if they’re in such a late disease process. To tell them, ‘hey, you live in long-term care. Your parents have passed away.’ You’re just traumatizing them all over again. It’s better to just live in their world. I might say, ‘Oh, your parents are just at work. They’ll be back anytime –you wait.’ And that’s a huge thing to just live in their world.”

“I feel like there needs to be more education on dementia,” Brianna says. With her specialization in behaviours, she knows sometimes interacting with residents takes a little extra time.

“On the weekend at the hospital,” she explains, “and everybody found this one patient difficult. But I sat with him for an extra ten minutes. And I learned that he lost his wife in February. I learned that he loves dogs. I learned that he loves to watch the news. Taking the time to talk to patients calms them down, builds their trust, and they end up not being so difficult.”

Another challenge Brianna mentioned is the need for more support in long-term care facilities. She and her colleagues can have 42 residents to care for at once. Spending 10 minutes with a resident is something she has to prioritize.

I tell Brianna that I’m grateful for our conversation. She has helped me understand long-term care from another perspective. I’m thankful she has the expertise I lack to help residents like Mum with her Alzheimer’s and dementia.

“You’ve seen it, right? This is my first time encountering it,” I say to her, speaking quietly about Mum’s Alzheimer’s. Brianna knows what we will face ahead – I do not. It’s reassuring to know we will have help.

“Absolutely. It’s a complete change. I get that,” she says. Brianna’s own mother, the amazing woman who inspired her to go into nursing, got ALS and died from it, she tells me. That was all new to her.

“I get it,” she says again quietly.

The nurses working in long-term care facilities aren’t just supporting the people who live there. They’re supporting all of us. And that’s a comforting thought.